3.10 Recommendations to the Norwegian Parliament on petroleum business in the Barents Sea and Sámi conditions

Einar Eythórsson’s report ‘Petroleumvirksomhet i Lofoten - Barentshavet og samisk forhold’ (‘Petroleum business in Lofoten - Barents Sea and Sámi conditions’) (2003) was one of two official recommendation reports produced on demand for the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy to consider how Sámi interests would be affected with an all-year petroleum activity in these areas. The lead author of this report Einar Eythórsson points out, both within the report but also on an independent science news website for Norwegian science, how he felt the time the research group was given was not sufficient to give a wholesome and representative recommendation report. He demanded at one point that as they had only been given less than 2 months to state all the risks involved for the Sámi with letting the petroleum industry near their coast, this could hardly be adequate to give justice to all the multiple effects that could come of this. The researchers demanded that they should either be allowed to print this clause in the finished document, or they would refuse to publish what they had gathered of information at all. The report ended up being printed with the clause, but regardless it was considered to hold enough information to form an official opinion on petroleum activity in the Barents Sea.

The report is based on what is considered the six Sámi regions, in total 17 municipalities in the Northern Norway. Except inner Finnmark, all the Coastal Sámi communities experience depopulation and shortage in traditional ways to make a livelihood. When planning where an eventual onshore land base for the petroleum could be located, it is important to localize where the Sámi have their settlements. The Sámi’s traditional fishing includes not only coastal and fjord fishing, but fishing in ice covered waters and in boats that can manage deep seas far from the shore. This needs to be taken into consideration when drawing the lines for what are Sámi interest areas at sea.

3.11 Oil spills under ice and health effects on Arctic humans

The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP) concludes in its final report ‘Arctic Oil and Gas 2007’ that oil activity can never fully be risk free, due to how tankers can spill transported oil, pipelines can start leaking, as well as accidents, even under the strictest of regulations. The social and economic effects oil activity will have for Arctic people, among them indigenous, are dependent on how involved the Arctic people is on decision making. The report recommends that prior to opening new areas for oil and gas exploration, or building the infrastructure to make these types of industries possible, the indigenous communities must be consulted so the negative effects can be held at a minimum and that the indigenous communities receive the maximum of the benefits from developing a new infrastructure. Their traditional knowledge can be used both for planning what areas to avoid building in, as these could be significant to the indigenous communities. How environmental monitoring has previously been done can provide a double security when what is available of modern technology equipment is combined with how the environment has used to change. When regarding how the indigenous might want employment in the oil industry, it is worth considering the effect it would have for a small indigenous community if the majority of the adult generation stops doing traditional activities as fishing due to a better salary in the oil industry. Generation gaps like this can have unforeseen effects on smaller communities.

On the effects oil will have on the environment and ecosystems of the Arctic, the report states how the Arctic surface environments are one of places on Earth that will show clearest evidence of alteration, and for the marine environment the main cause of change comes from oil spills. How oil behaves in Arctic waters is so unknown that a high sensitivity towards what the species already living there can manage must be the ultimate goal for any oil exploration. The Exxon Valdez oil spill continues to affect the environment for decades, and as there has currently been no major oil spill in the Arctic we can not know the long term effects.

Humans can be affected by exposure to petroleum hydrocarbons and this is mainly caused by an oil spill. The food security can also experience a risk of being altered either in quality, quantity or availability, this is directly linked to the state of the marine animals, as the main food source for most indigenous people living in the Arctic comes from the ocean, as the soil is too cold for agriculture. The overall picture of how petroleum hydrocarbons affect human health in the Arctic is complex at best.

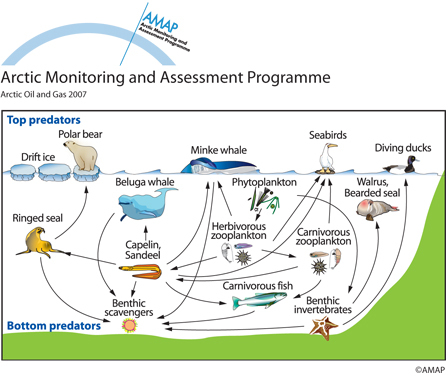

Oil spill response programs where ice is present hold a major challenge for all Arctic states exploring the option of oil activity. Most of the equipment suggested for use today were not designed to be used in an Arctic environment, and will therefore be inadequate when combating spills. This illustration shows the bio network of the Barents Sea (see figure 2). The whales in this area have needed a long time to grow in population size after centuries of hunting. It is only recently starting to pick itself up. Oil drilling and gas activity are the new threats facing the Barents Sea, and with such an abundant marine life the consequences of an oil spill could be hazardous.

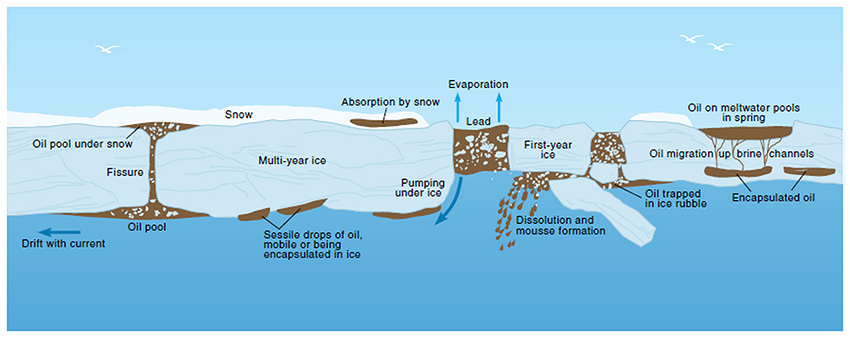

A key finding of the AMAP report is how there are no effective means of gathering or rinsing up an oil spill in broken sea ice (See figure 3). Oil spill responding in the winter adds to the impossibility as there will be no light between November and January (Arktisk system) and the darkness coincides with the harsh weather predictions of winter storms. If an oil spill were to happen in the winter on land or on the top of the unbroken sea ice, this would be easier to retrieve, as long as it can be finalized before spring time, when oil would sink under the ice. So far with the current technology the best recommendation from the AMAP study is to prevent an oil spill, rather than being dependent on an oil spill recovery system. The report suggests that this is still an area where new technology is needed, particularly for oil under ice and in broken ice, which might easily be the case if oil exploration takes place in the South-East Barents Sea, where the Ice Edge and Polar Front pose both of these challenges.

Figure 2: Simplified Barent Sea food-web The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP) ‘Arctic Oil and Gas 2007’

Figure 3: The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP) ‘Arctic Oil and Gas 2007’