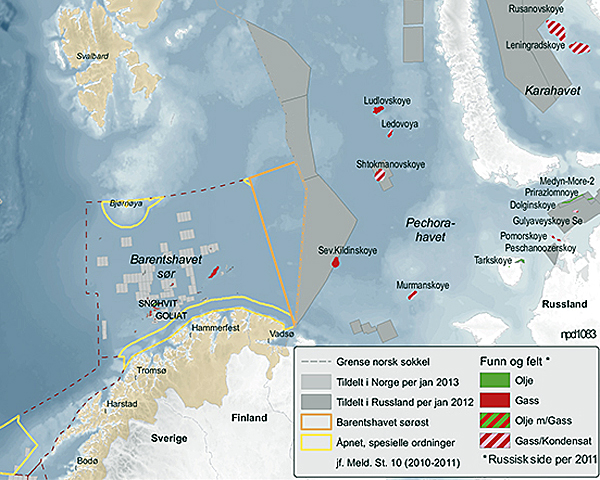

5. Has anyone informed specifically about the risks of an oil spill for you who live close to the South-East Barents Sea?

This was the one of two questions where the answers were unanimously ‘No’ with the most elaborate being ‘No, I miss information about this. It is we who have to live with the consequences.’ This single question can possibly be the greatest finding of this study, as for any nation wishing to do activities in a territory known to be inhabited by an indigenous population, The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN DRIPS 2008) states how the ‘Principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent’ should be applied. That information is not given directly to any of the 9 informants of this study can be explained with that information was given to the Sámi Parliament. However, what this dissertation argues is that it can not possibly be an informed consent at this stage, as

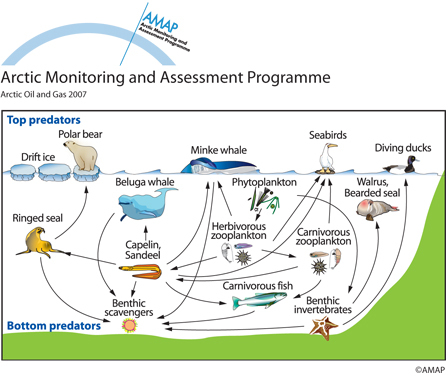

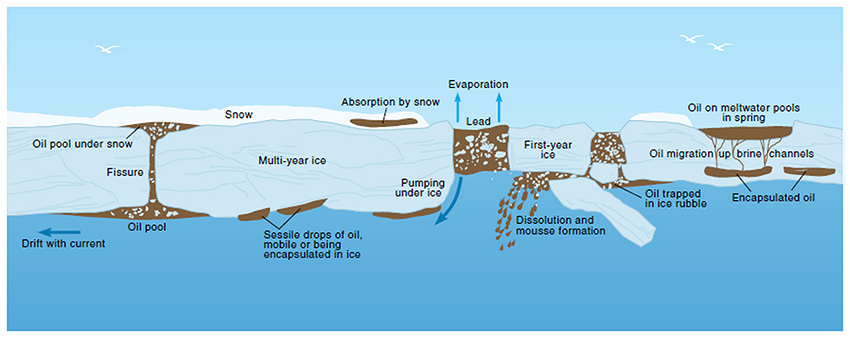

- There is no known way today on how to safely remove oil from ice covered waters. As the decision of regardless of this opening an Arctic area, the South-East Barents Sea, for oil recovery, an area that borders permanent ice, is therefore an uninformed decision, as the inhabitants cannot be given proper information on what might happen to their nature if an accident were to happen due to opening their territory to the oil sector.

- The marine bottom of the South-East Barents Sea is currently being mapped as part of the impact assessment done on the area, and this process is not estimated to be finished before 2020 (Mareano 2007). The decision to open the area up for oil exploration was still made, even though the Sámi populations heavily depends on what the findings might say on how the marine life is changing in population size or behavioral patterns.

As facts were missing in both cases, it can be argued that Norway breaks the international treaty they have signed in order to protect their indigenous population.

6. What thoughts do you have around a coexistence between the fishing industry and the oil industry; is it realistic?

The range of these answers came from a concern on how the oil industry might take over what was already there of the fishing industry;‘It is not realistic as long as there is a race towards getting the oil up.’ and ‘If the oil industry continues to grow it is NOT realistic. One should count less on the oil industry and more on the fishing industry. Let all of us in Norway come closer to nature!’ to the optimistic for coexistence ‘One has to adapt to everyday life. Cooperation and dialogue is key.’ The more specific answers were on the topic of seismic activity. One informant answered ‘The sound waves of seismic shooting when they search for oil scare the fish in a radius up to 34 kilometers from the area it is shooting in. And an oil spill would be a catastrophe. In the North there is a lot of bad weather, this can not possibly end well.’ On the same matter another informant replied ‘It is very problematic in my view. Not only does the frequent seismic shooting disturb the fish, but an eventual oil spill would be catastrophic.’ Both these concerns highlights how both the safe practice of doing oil searching activities may cause harm, but also how the overhanging threat of an oil spill would be severely detrimental for the fishing industry.

7. If repeated oil spills were to occur in your close environment, would this be a reason to move?

These answers showed a variety from the ones who did not see moving as a possibility; ‘No. My home is way to close to my heart. Besides, someone has to stay here and protest against the oil industry.’ and ‘Not for me and my family, but for many others. And if it was not a reason to move it would still reduce the life quality of many.’ to the ones willing ‘Of course, one does not wish to live in an environment that is contaminated.’ and ‘Yes, it would reduce the wellbeing of living in my close environment.’ but the answer that highlighted this debate the most was the informant who raised the very relevant question‘Yes, but where can one move? It is one thing to think that you can just move if the nature surrounding you is destroyed, but if all the world’s population gets their areas destroyed of modern non-renewable and capitalist driven industry were to move it would be total chaos.’ As more people have become refugees due to the changing climate than there currently are refugees caused by war (Regjeringen 2013), these are alarming prospects that the informant raise.

8. Do you experience a great awareness in your local community around what an oil spill would mean for your close environment?

The tendencies from the answers points towards that the environmental concerns are known but not discussed in the public debates on oil in the Barents Sea. ‘Yes, but this does not show in the public debate. It is only characterized by the hope of growth and prosperity.’ and ‘There exists a conscience about the consequences. But one does not talk about it.’ There was also one informant who replied that there was a lack of awareness, and instead of this there were hopes that the oil industry might bring more workplaces than what already exists; ‘No, people think that there will be more workplaces. They don’t think about the ones who are likely to lose their workplaces, such as the fishers.’

9. Are you familiar with the oil spill recovery situation of an oil spill where you live, and how long it would take from the oil spill until the emergency action was operative?

This was the other question where the unanimous answer was ‘No’, with one informant adding the concern on the technology available today: ‘No, I have no knowledge on this. Except that it works very poorly today.’

10. Have you participated politically in the relation to the oil drilling in the South-East Barents Sea?

This question caused many answers along the line of ‘In no way.’ except for two of the informants who replied ‘I am a local politician. But if there are plans of a demonstration towards the oil industry, of course I will join.’ and ‘I stood on a list under the last Sámi Parliament election. I am a member of ‘Nature and Youth’(Environmentalist organization). That only 2 out of 9 informants had participated politically against oil drilling may have a variety of factors, one of them being, based on the answers in question number 8 on awareness, that this is currently not a political matter.

11. In your opinion, what would you say weighs more heavily in your local community: The ecosystem of the ocean, or a possible financial growth due to the oil recovery?

The majority of the informants answered that a healthy ecosystem in the ocean is the main factor in their close environment‘To preserve the ecosystem intact is the most important factor.’, however informants were worried that this was not always the case for the political decisions‘The ecosystem in the ocean should weigh the heaviest. The fish would give work to many more. Sadly it doesn’t due to political reasons, or political weakness.’ or the majority of the inhabitants ‘For me it is the ecosystem, but I think for the majority it will be financial growth.’ An important question was raised when one informant asked ‘The ecosystem in the ocean. As long as the fish exist we will always have food. Isn’t our economy good enough?’ Is the economic need for oil of greater value than securing the fishery industry, an industry which in 2010 contributed with 46,5 billions NOK (Sintef 2010) to Norway’s GDP?

12. Are you familiar with the problems connected to gathering oil in ice covered waters, as next to the Ice Edge and the Polar Front?

The majority answered negatively ‘No.’ to this question except for one informant who was familiar with the problematic nature of oil near the Ice Edge and Polar Front‘Yes, it is unique and vulnerable nature and animal life there. Sea scientists and environmental experts warn against it.’Another informant contributed by stating what is the general consensus on oil recovery in ice covered waters ‘Yes. I am familiar with it and know that it is near impossible.’

13. Is there anything else about oil recovery in the South-East Barents Sea that engages you that has not been raise in the earlier questions?

One informant had a valuable point on food security that had not been directly addressed in the previous questions‘I fish all year around to collect food. If the fishing had been equally as good as it was 20 years ago, I would have made fishing my life stock. There are few who eats more fish than me. I never buy fish or meat in the store. The most important fish species in quantity here is the cod. It is mostly fjord and coastal cod, but also arctic cod. If a bigger oil spill were to occur an entire year of arctic cod could be extinct. That affects my opportunity to collect food. As of today the consequences would not be that big, but in 10-20 years time, when I am sure that the food prices will have risen, then a decrease in the cod population will have a major impact for me. The time perspective for the food security needs to be longer than the foreseeable future , and this informant addressed how an oil spill could possibly make an entire year of arctic cod become extinct due to pollution.