3.9 The added factor of climate change

The IPCC has concluded that climate change is happening twice as rapidly on and near the poles, as the rest of the globe. This makes climate change unavoidable to mention when considering how the Sámi population will be affected by a possible oil spill in their immediate nature. The ACIA report (Arctic Climate Impact Assessment 2004) concludes that the consequences for societies living in the Arctic of climate change will include:

- Loss of hunter culture: Because of the melting all year long ice several species that are reliable on this ice for resting are likely to become extinct, causing difficulties for the Sámis dependance on these animals. The loss of their hunter culture will not only take away a traditional source of nutrition, it is highly intertwined with their sense of cultural identity and what it means to be Sámi.

- Reduced food security: Access to traditional food as seal, polar bear, reindeer and some fish and bird species are likely to diminish as a consequence of the heating. Reduced quality and illness among the fish and in the berries that the reindeers eat are already being observed. With the shift to a more ‘Western’ nutrition comes an increased chance for diabetes, obesity and heart diseases.

- Health concerns for the inhabitants: Thinner ice caps is a direct cause of the changing climate. This can be dangerous if the Sámi continue to use their traditional paths leading over ice covered-shores that used to be safe. The melting of the permafrost can also lead to poorer sanitation facilities.

- Consequences for the herds: As changes in what routes are possible for the reindeer, where they can give birth and access food will be altered, the likely scenario is that this added stress will have a negative effect on the reindeer herds, leading to thinner reindeers with a decreased estimated life span, which again will affect the Sámi in a negative way.

- Increase in ship traffic: As the year long ice will melt, new sailing routes will be possible. The North-West passage has already seen an up-rise the last couple of years and within the end of the century this is estimated to be the preferred shipping route of goods. The positive consequences this will bring are more tourism to the Arctic countries, with a possibility that the Sámi will get more attention and a possible market for their livestock. The environmental aspect of more ships going through the Arctic waters is the increased likeliness of introduced species that are highly likely to come along with the ballast water being emptied in the Arctic with water from more southern areas. The introduced species are likely to compete with the ones who are already accustom to the environment, and the consequences on the ecosystem as a whole are hard to predict when introduced species enter an already complete ecosystem.

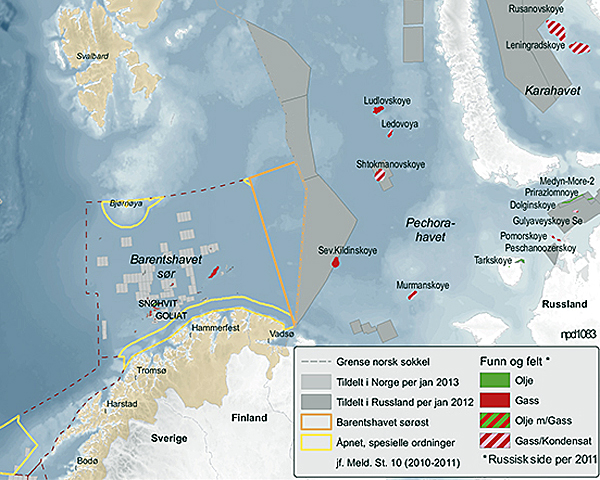

- Increased access to resources: With the melting of the ice in certain areas, former impossible places to search for and extract oil and gas will be possible. The moving ice will also cause an added danger for the petroleum searches in these areas, as the ice is no longer stabilized.

- Extended fishing opportunities: Key farming fish species in the Arctic, as herring and cod are likely to thrive in a warmer environment, but it is also very likely that the traveling patterns and prevalence areas of many fish species will change.

- Difficulties of transportation on shore: Transportation across the land and pipelines are already being affected by the melting ground. This is likely to increase. Settlements that are dependent on ice covered or frozen roads in order to be accessed for supplies will suffer.

- Reduced freshwater fishing: By the end of this century it is estimated that a number of species that have adapted to life in Arctic waters will become extinct both locally and globally.

- Better terms for agriculture and forestry: The opportunities for agriculture and forestry are likely to increase, as the warmer weather will open for growing food and trees that former only could live further South.