3.5 Food Security for the Sámi and the Health of Species living in the Arctic

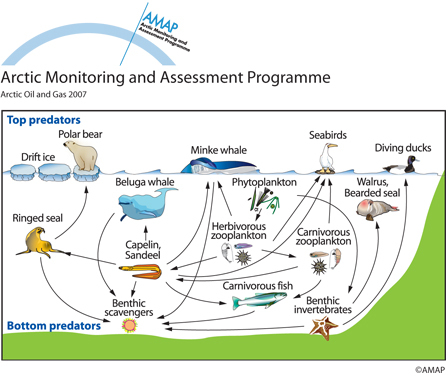

The Arctic Council and Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) writes in the extensive report ‘Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic: Effects and Potential Effects’ (2007) on how seals and whales are normally not that sensitive towards outer affection of an oil spill. This is due to their thick layers of blubber that protects them against heat loss, and the skin of whales and walruses are robust enough to not take harm from contact with oil. Baby seals with fur however are very sensitive towards oil, equally so are polar bears, sea otters and Northern fur seals.

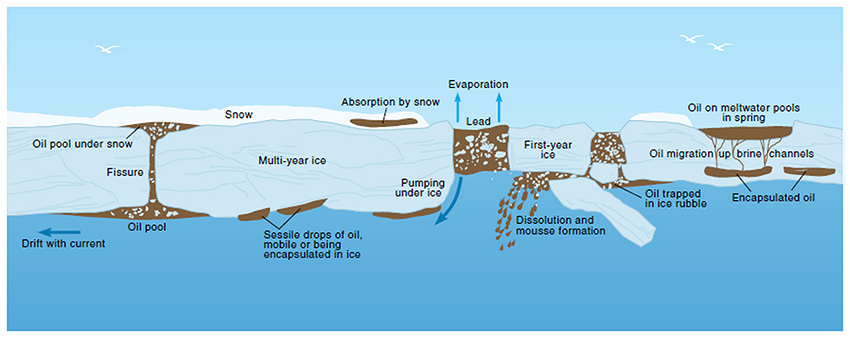

The report states how oil spills in ice covered waters will be severely difficult to rinse up and with the added potential that the oil stays for a long time in the waters. Important areas where sea birds come to hunt for food and whales and seals comes to breath are openings in the ice, such as reads and so called polynyas, which are ice free areas due to wind and leeward sides produced by islands. Because of the need for keeping these areas free of oil, the whales are also considered sensitive towards oil spills. In all areas where birds and mammals appear densely packed in the Arctic will be areas that are vulnerable towards oil spills or disturbances from the petroleum industry.

3.6 The formal process of opening the South-East Barents Sea for petroleum

The State Report ‘Meld. St. 36 (2012-2013) Melding til Stortinget Nye muligheter for Nord-Norge - åpning av Barentshavet sørøst for petroleumsvirksomhet’ (‘Message to the Parliament New possibilities for North-Norway - opening of the South-East Barents Sea to petroleum recovery’) is a recommendation report written on the basis of the impact assessment done by several affected actors, among them the Sámi Parliament representing the interest of the Sámi population when considering whether it is responsible to open the South-East Barents Sea to the petroleum industry. The chapter of the impact assessment regarding how the Sámi interest will be affected is based on an independent study done by the consultancy firm Pöyry (2012) that considers the Sámi’s commercial activities such as reindeer husbandry, fishing, rural livelihoods and forest pasture, in addition to employment, competencies, settlements, expression of culture and identity development. The scenarios that are considered in this assessment are only the effects on the Sámi population during ordinary petroleum activity, meaning without any leaks or other emissions to their close environment. This is the gap this master is trying to fill; what if something goes wrong?

Chapter 8 ‘Betydningen for samiske forhold' (‘The Significance for Sámi conditions’) in the report ‘Ringvirkninger av petroleums- virksomhet ved Barentshavet sørøst Konsekvensutredning for Barentshavet sørøst Utarbeidet på oppdrag fra Olje- og energidepartementet’ (‘Ripple effects of the petroleum activity in the South-East Barents Sea Impact assessment for the South-East Barents Sea commissioned on behalf of the Ministry of Oil and Energy’) considers how Sámi interests are affected. Sámi areas are all the areas that the Sámi use or live in, practically speaking this covers all of Finnmark, northernmost municipality in Norway, as a Sámi area. The Sámi way of making a livelihood involves reindeer husbandry, fishing, rural livelihoods and forest pasture, of these the fishing, rural livelihood and forest pasture will be affected by the petroleum expansion, both for the Sámi and non-Sámi population. The petroleum industry’s impact on the reindeer husbandries will however only affect the Sámi, as they are the only population in Norway that exercises this. It is only a small number of the Sámi population that exercise reindeer husbandry, although it is considered a significant part of Sámi culture expression and identity. An explanation to this can be found in Vistnes et. al. (2008) where it is suggested that the reindeer husbandry has in a lesser degree been ‘Norwegianised’, as for example the Coastal Sámi culture has experienced. The report looks on the direct consequences the petroleum expansion will have for Sámi livelihoods. There can however also be indirect consequences given that the Sámi and the petroleum industry will want the same employees, and as the Sámi’s way of cultivating their land is so closely knit with their expression of culture and identity, this can present a challenge. As this master focuses on the Coastal Sámi in particular, it will only very briefly touch upon what the effects of the petroleum industry can lead to with the reindeers. Local direct effects, as building a road necessary for the petroleum expansion through a grazing area, can lead to disturbance of single reindeers as increased stress may shorten their life expectancy. Regional indirect effects on the herd as a whole can occur if reindeer shun the areas where they know they are likely to be disturbed and because of this they end up being rounded up in smaller grazing areas, where they may over-stretch the capacity of the given land, causing the reindeer to not gain as much body reservoirs as is necessary before the cold season. The cumulative long-term effect of the production is reduced health for the reindeers, leading to a fall in the reindeer husbandry for the herding Sámi population.

When considering what areas within the fishing industry that are considered of Sámi interest, the general consensus is that the Coastal Sámi population has mainly focused on fishing in the fjords and nearby coastal districts, even thought many Sámi participate in fishing off shore with active fishing equipment. On this basis these sources suggest that it is not purposeful of the impact assessment to make a divide between the Sámi population and the non-Sámi population in questions regarding how the petroleum will affect the fishing industry in Finnmark. The breeding industry for fish has become an important industry in many fjords with Sámi settlement, which has caused the breeding industry to be counted upon as a Sámi industry. The way fish will be affected by the petroleum will in turn have direct consequences for the Sámi conditions.

The Sámi's use of agriculture and forest pasture is a traditional part of the Sámi living. In addition to reindeer husbandry, their livelihood also includes grouse hunting in the forest pasture and fishing. Today, these are only considered subsidiary income sources for the Sámi, with a difficulties recruiting. However, the agriculture is very important for Sámi families, as the family is an economic production unit, and places where the Sámi can fish and hunt are considered important factors for where to make settlements, in addition to being culturally important. The way Sámi agriculture in Finnmark would be affected in a high risk scenario of the expansion of the petroleum industry would be if Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) (see Glossary) constructions were built on shore that took up the areas where the Sámi traditionally have done their hunting, or where they have their settlements. In addition comes the possible pollution the construction can have on the outskirts. In a low risk scenario the petroleum constructions would be off shore. This would lead to a lesser impact on the Sámi settlements, although it opens up to a range of other potential threats of how petroleum construction sites at sea can harm the environment that in turn will harm the Sámi through their fishing.