2.4 Interviews

1. What do the coast and the ocean mean for you and your livelihood?

‘The ocean means I always have access to food. My ancestors were poor, but people along the shore have never been starving, because they could go out at sea and fish.’

The aspect this informant highlights draws attention to how the people of the North do not only eat fish as a supplement to their diet, but how fishing both traditionally and today are the main source of food. Any insecurities around the food security are therefore of a great concern to the inhabitants with direct access to the Barents Sea.

‘The coast means incredibly much to me as a Costal Sámi. The ocean and the coast are the very foundation for Sea Sámi Culture. Without the coast and the ocean it is hard for the traditions to have a continuity.’ When discussing land and sea resources when indigenous communities are involved it is not the same question as discussing relocations for non-indigenous, although it is of course problematic for anyone who would needed to be relocated due to changes happening in their home environment. For the Coastal Sámi in particular, the closeness to the sea is one of the last remaining aspects of their cultural identity, as one informant informed me the Norwegian assimilation process were particularly hard on the Coastal Sámi.

‘Without the ocean, where should we get fish? If I live away from the ocean too long, I miss it. There is something missing. I did not understand this when I was a child, when my mum said she could not live away from the ocean, but when I moved to the inland for a year I understood it.’ Both the food aspect and the identity dependency on the ocean are equally strong components for this informant in the relationship to the ocean.

‘I grew up by a fjord, and have learned how to walk there and use the resources that exist in the ocean. Fishing is important both as food gathering and recreation. And I have a strong place belonging to the fjord. Here have my ancestors lived, and it feels right that me and my children use these same areas and to harvest what the ocean gives.’ This bond to their nature and the generation aspect of why this place in particular is important is one of the ways indigenous communities as the Coastal Sámi explains how they are un-separable from their nature, because who they are is so intertwined with who their ancestors were due to where they lived and were shaped by nature.

‘It is a very important part of my everyday and my life.’ Simply put but very efficiently this quotation says how the ocean is something that plays a significant part both on an everyday scale, but also for the more long term perspective.

‘For the immediate livelihood the coast and the ocean not so much. But I have grandparents who subsist of what the ocean have to offer, with both sea salmon fishing, cod fishing etc. But, for one who is raised by the coast, I need the ocean on another level. I can not imagine living a place where I do not have immediate access to the coast and ocean.’ This informant does not make her livelihood of the ocean, but is equally tied to it. This ‘another level’ she speaks of is an indicator to what the ocean has to say for how her identity is so closely linked to the ocean that living another place is not thinkable.

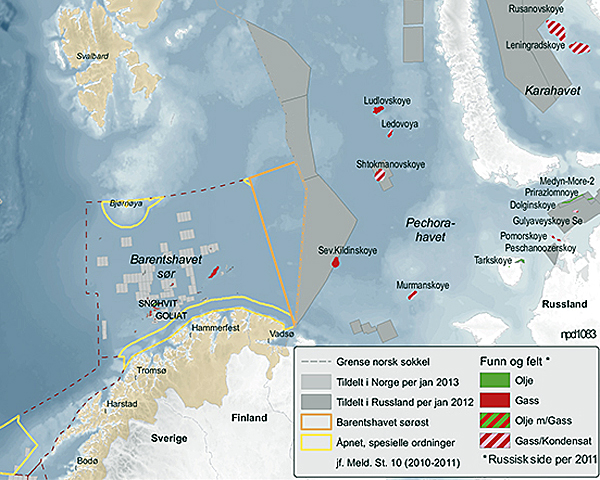

2. Have you been following the debate regarding Norwegian oil exploration in the Arctic (recently around ‘Bjørnøya’=Bear Island)

The answers ranged from five ‘Yes’ to four ‘No’, with the most elaborative answers explained ‘That I have. That they even plan a new drilling in the Arctic is frightening.’ This remark shows the concern of the informant, and implies an awareness of why Arctic oil drilling is problematic. Another concerned positive answer was ‘Yes, that debate I have been following. Not only because I work with Sámi issues and land and resource rights, but also because I am concerned about protecting a healthy coastal line.’ This indicates that the informant thinks oil exploration could interfere with a healthy coastal line.

3. What is your view on oil recovery in the South-East Barents Sea?

This informants show a precautionary attitude towards oil recovery due to the protection on the known values as a clean environment and the fish.‘I am very skeptical of oil recovery in the Barents Sea. I fear that the environmental consequences can be large. Is there a hurry to get the oil up? After all, it does not disappear. Oil is a one time resource. The cod is renewable.’

Both these two informants seem to have the climate change impacts in mind when considering if oil recovery in the Barents Sea is necessary, as burning of fossil fuels is a documented source of contributing to global heating (Nasa). ’One has to try to develop another alternative to oil and gas. There is no future for our planet if the recovery of all these fossil fuels continues.’ and ‘It should be completely unacceptable both because of the danger for the nature and because oil and gas production ought to diminish, not increase.’

‘I do not see why we should take the risk. The consequences of an oil spill would be catastrophic for the fragile environment of the North. I think we should save the none renewable resources to a time when we maybe really need them, and rather count on finding more and better renewable ways of getting energy.’ The precaution this informant advocates goes along the line of what environmental agencies of the Arctic recommends, as WWF’s recommendations on Arctic oil and gas is to leave it be (WWF).

Another perspective is that of bringing the financial growth Norway’s oil history has undeniably brought the country more localized to the Northern part of the county where this oil would be extracted: ‘The oil industry has good ripple effects on the business and the infrastructure.’

One informant chose to not take a definite stand on whether they were for or against, but showed a concern for how the oil recovery might interfere with this highly adapted nature. ‘I can’t say I am either pro or against. But, I have great concerns about a possible oil recovery in such a climate exposed area.’ The term ‘climate exposed’ refers to how the Arctic, although hostile with its extremely low temperatures is actually a highly fragile environment and one of the places on Earth that most easily would be affected by human interference (GRID 2014).

‘I am against oil recovery in the Barents Sea for as long time as the relationship to the Sámi rights and Sámi interest in the area is not clarified.’ This statement stands for the protection of Sámi rights, as discussions on how to distribute areas where Coastal Sámi people have traditionally lived has not yet begun.

4. What consequences would an oil spill have for you and your close environment?

This informant describes how her everyday activities connected with food gathering, especially from the sea, will suffer if oil was spilt in her close environment. ‘It would have great consequences. We use nearly all the animals in the sea and along the coast. We fish all year around and in the spring we go out on the islands and collect seagull eggs. In the late summer we pick all sorts of berries on the islands. An oil spill would have caused a break in our living traditions.’

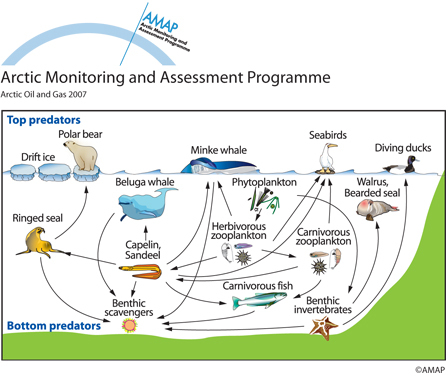

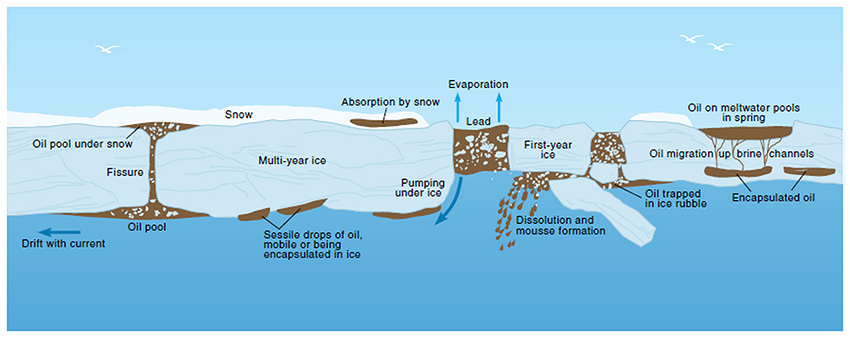

The holistic approach to oil spills can be seen in the two following answers; ‘It would have enormous consequences for the areas I stay in for most of the year. For the animal and birdlife, for the fish, for the humans and the entire ecosystem. These are frightening perspectives.’ and ‘It would be catastrophic for those who live of the fish and the animal life.’ Both answers stand as a testimony to the uncertainty that surrounds Arctic oil spills, as neither the industry or environmental agencies can produce a definite answer as of today on how to safely remove oil from ice covered waters (WWF Canada 2011).

This answer is more concrete and describes what the informant think will happen when the oil meets the shore. ‘An oil spill that causes the oil to come right onto the shore will bring an ecological catastrophe, and ruin the close environment for the unforeseeable future.’